Classroom Culture

(1) coaches and reinforces peer-to-peer dynamics that are appropriate and constructive

Constructing a student-centered, discussion style classroom is built upon collaboration, relationships, trust, and a sense of community. Learning is a vulnerable act and to put one’s own thinking, creation, and/or ideas on display publicly necessitates the creation of an intentionally designed safe space and classroom culture in order for students to feel comfortable enough to do so.

Collaboration is central to my classroom culture. This can range from informal think-pair-shares and turn and talks to fishbowl discussions and jigsaws to peer-to-peer writing workshops. While each activity is carefully selected to support student learning for that particular day’s lesson objective, they are also utilized to promote positive peer-to-peer dynamics that allow students to learn from one another and support each other in their endeavors. However, simply implementing an activity does not necessarily mean that it will produce the intended results. Putting groups together for 9th graders may require additional scaffolds and supports than necessary in a 12th grade classroom.

In group activities, creating specific roles provides more structure for students to collaborate in a productive manner. Students are equipped with a specified task while also seeing how their assigned component and contribution is crucial to the group’s success. Here is a group role assignment in Boundaries where students, who all served as a different expert, were advocating at a townhall event for different anti-Apartheid tactics:

| Anti-Apartheid Townhall | Organizing your group: Each member of your group will take a specific role. Below is a brief explanation of the responsibility of each role. Before preparing your sections of the presentation, work together to address the questions below. The group director is responsible for organizing the presentation of your group’s option to the Cape township residents. The domestic political expert is responsible for explaining why your option is most likely to succeed in the current domestic climate. The international political expert is responsible for explaining why your option is most likely to succeed given the international opposition to apartheid. The historian is responsible for explaining how the lessons of history justify your group’s option. |

Sharing your writing with others can be extremely intimidating. Providing good and constructive feedback can be difficult, especially when you are also learning to improve your own writing. In order to maximize productivity during peer-to-peer conferences, it is vital to give students the tools necessary to participate in this specific form of discussion. Here, both the author and editors are provided sentence starters to help start the conversation and keep it substantive and concrete:

| Peer-to-Peer Conference | [Author] A challenge might be: “I am having trouble making this specific,” “I don’t really have enough information for…”, “It’s hard to organize this paragraph”, “I’m not sure where I should define this term”, “I’m not sure it makes sense”, “I’m not sure if it reads well”, etc. [Editor] CLARIFYING QUESTIONS: Clarifying questions asked by the editor: Clarifying questions are simple fact questions in order to understand the challenge more appropriately. A clarifying question might be: “I don’t understand this word”, “Can you explain this part of your thesis more,” “What really interests you about this topic?” The presenter listens and makes notes of the questions. [Editor] PROBING: The presenter answers a the questions and engages in a deeper conversation with the editors. The editors may ask deeper questions and begin to dig deeper into the issues raised by the presenter or issues discovered by the editors. The editors and author try to develop a shared understanding of the challenge and its complexity – What did you hear? What didn’t you hear that you need to know more about? What can be built on/what is missing? “It might be interesting to explore…” “I wonder what would happen if…” “Perhaps you have thought about this, but …” “A question this raised for me was…” “One of the things this got me thinking about was…” “Observing the class made me more aware of the tension between…? “A concern raised for me was…” |

(2) communicates behavioral expectations that are appropriate to class activities

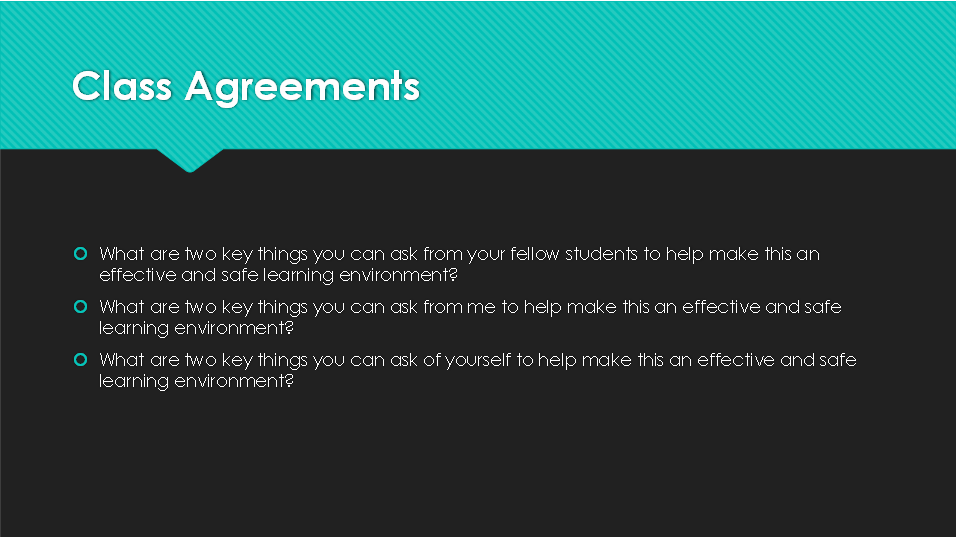

Some teachers like to frontload expectations on the first day of class, whereas other like to start with a ‘hook’ lesson. I’ve tried both approaches and have typically found myself orienting towards the latter. Having an engaging lesson on the first day can really help to set the tone for the term. From there, I work to build in expectations by starting with broader framing and inviting student input in class norms. When students are treated as stakeholders and are allowed to help shape the classroom norms and culture, there is ultimately more buy in.

Further expectations will be covered as they arise with introducing new activities, like the first Harkness discussion, research day, or group project. Before jumping into the discussion, I will survey students for norms and best practices. When I get generic answers like ‘respect’ I will follow up with questions like “What does that look like?” or “How do we know this is a respectful discussion?” Often, I will stop after a few rounds of contributions and have the students start to reflect on what is going well and where areas for improvement exist. Having them consciously reflect on the activity and process in the moment, reiterates the expectations and ultimately elevates the overall quality.

It is important to keep in mind that these are still young people and there will be slip ups from time to time. A well organized lesson is usually the best proactive measure to meet student needs and keep a high level of engagement. When designing a lesson, I consider the ratio of how much I am speaking compared to the students, how varied my activities are, and the balance between individual and collaborative opportunities to think and reflect. When students do not meet expectations, I warmly redirect behavior. I start with proximity and non-verbal cues that are subtle like tapping on the desk as I pass by. If verbal redirection is necessary, I approach it as general reminders without singling out individuals, like “Let’s make sure our attention is back up front,” or “Let’s make sure we are giving our classmates the attention they deserve,” or “[insert student name] might be asking a question that would benefit everyone.” If I am noticing a pattern with an individual, I will seek a one-on-one conversation. In a recent check-in, I noted my growing concern about some persistent behaviors. I framed the conversation as not one about consequences, but to better understand how I could support them in class. The student appreciated the intention and explained their exhaustion and struggle to focus when our A block was the last class of the day. We collaborated on some different strategies that would help them redirect their behavior and stay focused without feeling called out. This student has been engaging more and participating on a more consistent basis. I was sure to note this in their midterm comment and also acknowledged their efforts after class too.

(3) develops a mutually respectful relationship with each student, instilling confidence that the teacher is invested in their success

Relationships are central to my teaching practice. Not all students are going to be intrinsically interested in every subject or every particular topic taught. However, when students feel respected, known, and cared for, they are more willing to invest in the learning process, more fully engage in the lesson, and allow themselves to be more vulnerable.

I try and take simple steps in building relationships with each individual student by welcoming each of them to class with a genuine excitement, asking them questions about their personal lives during the passing period, acknowledging them in some form outside of the classroom, and genuinely taking an interest in them as people. From time-to-time, I will also start with an elaborate and absurd attendance question, like:

For reasons that cannot be explained, cats can suddenly read at a twelfth-grade level. They cant talk and they cant write, but they can read silently and comprehend the text. Many cats love this new skill, because they now have something to do all day while they lay around the house; however, a few cats become depressed, because reading forces them to realize the limitations of their existence (not to mention utter frustration of being unable to express themselves). This being the case, do you think the average cat would enjoy Garfield, or would cats find the cartoon to be an insulting caricature?

(Chuck Klosterman’s Hypertheticals)

These types of prompts allow for time and space to be silly and playful and allow the kids to express themselves as kids. New inside jokes can be formed and referenced in relationship-building. Furthermore, this gets the students engaging with one another and willing to share out. When students are able to laugh at themselves and laugh with one another, for those whom discussion and participation is intimidating or anxiety-inducing, this helps to ease that feeling and to feel comfortable within the classroom community. As more typically shy and reserved students find the confidence to participate, I make it a point of emphasis to acknowledge them at the end of class one-on-one and to encourage them to continue to make these efforts. That recognition can instill confidence and reinforces their trust in me.

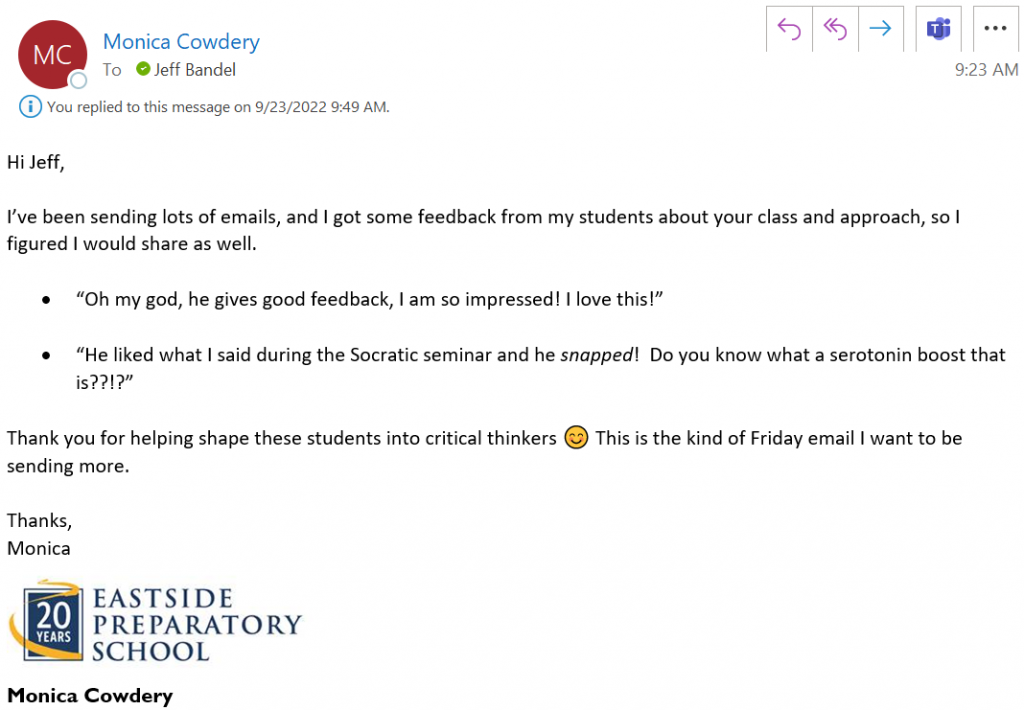

This balance of fun, authentic efforts in getting to know them personally, and development of trust allows for more honest conversations about student progress, skill development, and performance. Rather than seeing feedback as judgment or documenting their imperfections, the trust in our relationship allows reception of feedback because they are able to see my investment in their growth as individuals and students.

I was very proud of Andy for making the effort to set up this meeting, but even more so for how the meeting went. While Andy was disappointed in his grade, he did not approach this meeting with any intention to advocate for earning points back or to argue his overall grade. He wanted to ensure he understood where he could improve, what that would look like in the context of his submission, and ask additional clarifying questions. Andy’s overall performance this year has dramatically improved from fall to winter trimester.

(4) demonstrates cultural competence by promoting inclusivity

Operating a student-centered classroom puts their thinking, their reflections, their insights, and their stories on display by design. This requires careful and intentional selection of texts, curation of questions, and structuring of activities and assignments. With the diversity at EPS in our students’ varied learning styles, experiences, and backgrounds, allowing students to speak from the I perspective enriches the overall classroom experience and each classroom member benefits as well.

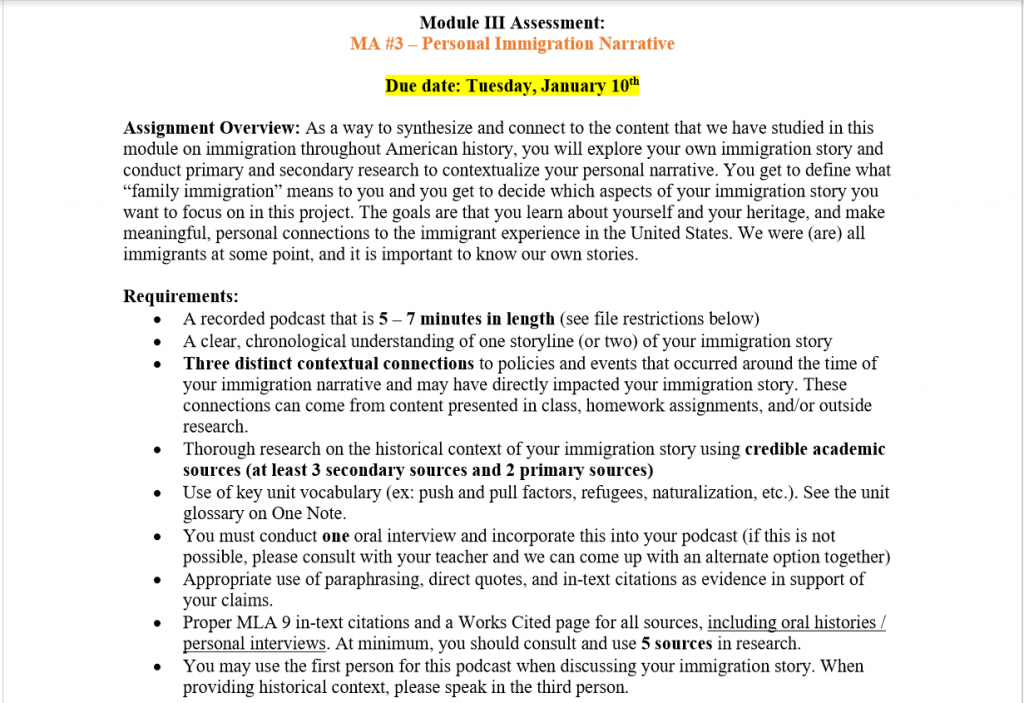

One of my favorite projects in US History is our Immigration Podcast.

Students are prompted to learn about their own family’s history and relate it to our module on immigration history in the United States. This adds more personal stories within the content we study, helps to build empathy and cultural appreciation, and adds additional levels of complexity to the historical narratives that we present. Most importantly, it allows students to understand who they are even more so. Students are asked to interview a family member about their family’s immigration. Sometimes this is the relative who actually went through the immigration process or sometimes it’s a relative sharing a journal or document from someone who came over on the Mayflower. Each story is incredibly unique and valuable and allows each student to see their own history within the course. I always love to hear from the students how much they learned, interesting bits of family history, and their overall appreciation for the experience.

History classrooms often have to deal with difficult subject matters. Whether it be in response to a current event or covering the various injustices throughout human history, it is vital to include students into the discussion about the learning experience.

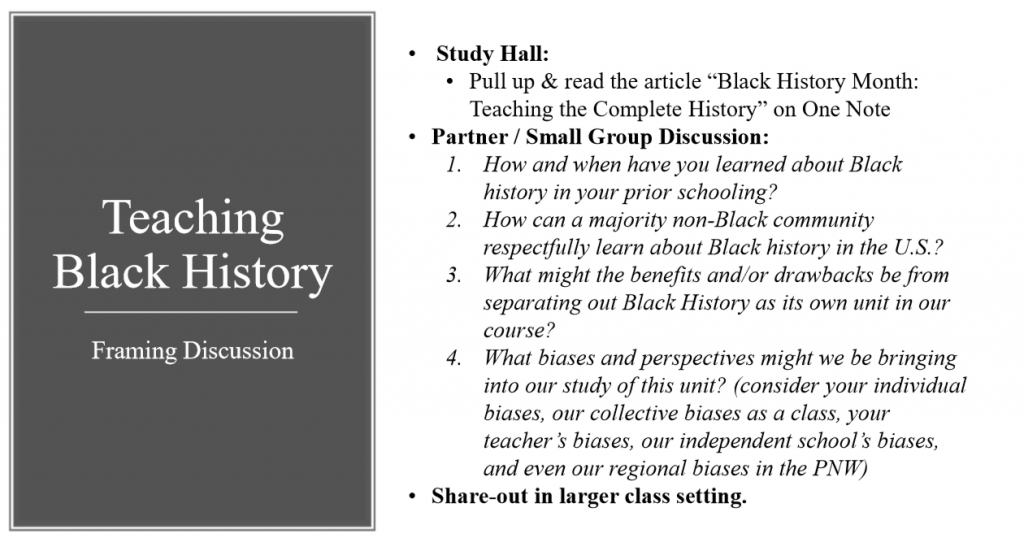

On the first day of our Black History module in US History, we framed the conversation by surveying the class on their individual experiences learning about Black history, acknowledging the identity dynamics, and examining the impact of curricular decisions both on how we teach and how we learn this particular topic.

Before having this conversation, students were asked to read an article from Learning for Justice on teaching Black history (Learning For Justice–Black History). I communicated with the students that some of the ideas in the article were at the forefront of how the US History team was designing this module, acknowledged where some limitation existed like time and what we were covering, and my own identity and what that meant for teaching Black history. Students were able to express why this approach of going beyond simply a narrative of violence and victimhood was critical, shared stories from their own educational experience of limited inclusion or oversimplification of Black history, and an acknowledgement of their own biases. With this framing, students have been able to handle the content with the maturity and sensitivity it deserves, appreciate our mutual respect by including their input, and allowed themselves to be vulnerable in sharing their own biases and perspectives.

(5) designs and facilitates a classroom culture that promotes student preparedness, engagement, self-advocacy, perseverance, and collaboration

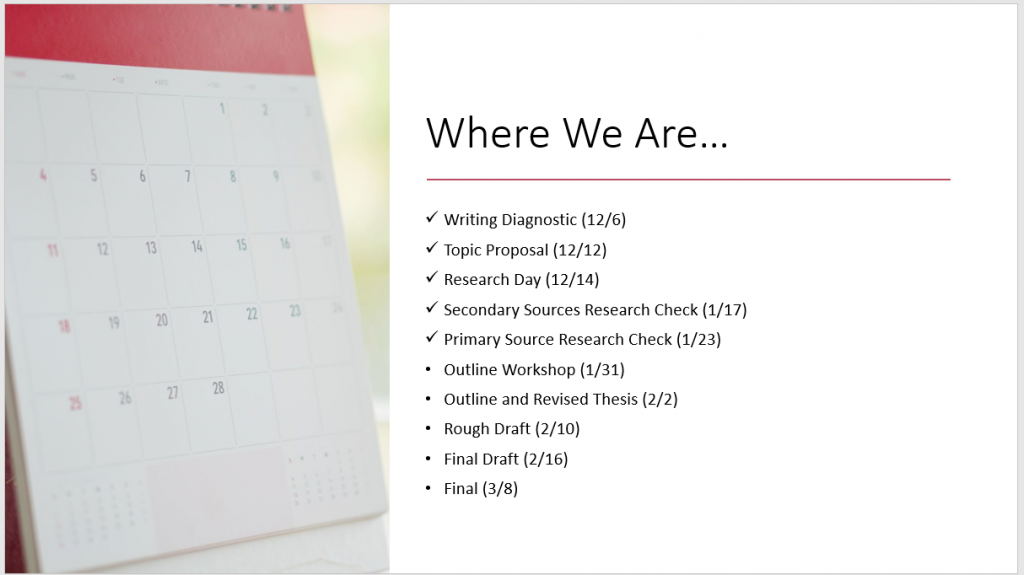

There is a wide array of ways that I facilitate and establish a classroom culture that promotes engagement, collaboration, and self-advocacy. In addition to these priorities, I also work to foster student preparedness and perseverance. Both 9th grade humanities course offerings during the winter trimester focus on argumentative writing. Having student develop a research question, consult a variety of primary & secondary sources, and construct an argumentative essay can be quite a daunting task. To help students persevere, we have broken down the writing project into a step-by-step format where each assignment helps students move through the process equipped with feedback at every milestone. For transparency sake and reiterate that this is a process, I will have the class take a moment to check-in on where we are, to appreciate what they have already accomplished, and remind them how each step helps to get us where we need to be.

Furthermore, this scaffolding allows for students to not get lost in the magnitude of the task. It breaks it down into targeted segments that allows for better focus and preparedness.

Pedagogical Effectiveness

(1) begins class sessions with a clear statement about the lesson’s objectives and place in the progression of course

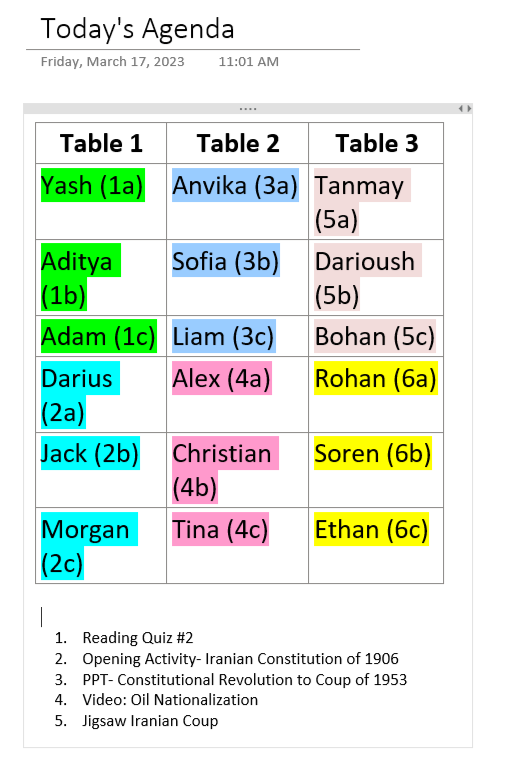

Students are creatures of habit and while I want to balance routine with a class that is exciting, fresh, and new, particular elements allow for students to better be set up for success that specific day. One of those is starting class with that day’s agenda posted in a consistent manner in OneNote.

I start each class off with a daily agenda. This serves as preview for the day, signals to students that class is starting, and also provides them time to access the necessary materials for class.

- On this particular day, students had a reading quiz on an important chapter. I used this as a formative assessment to ensure students had a baseline understanding on key ideas and concepts related to Islam and its development. With the quiz data on Canvas, I will do a reteach on the frequently missed questions. Students performed at an average of 85% and only some minor misconceptions will need to be addressed.

- Following the reading quiz, students worked individually on the opening activity. Typically, this is how class starts and is utilized in a variety of ways: (1) Prompt student thinking on something relevant to that day’s lesson, (2) review previous content and address any misconceptions, (3) make connections to course material, or (4) begin to hypothesize for that day’s inquiry. On this particular day, I had students individually create a list of Western enlightenment ideals and Islamic beliefs that could possibly influence the development of the constitution of Iran in 1906. From there, students then analyzed selections from the constitution for evidence of these two influences.

- Since this was a lesson early on in the term, I was providing a lot of the contextual pieces for our study of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and presented a lecture in PowerPoint form, which was supplemented with a video on the nationalization of Iranian oil.

- Students were then tasked with a jigsaw from a variety of sources on the 1953 coup and asked to make sense of what really happened.

Snippet from Anne Duffy’s classroom observation:

| (5) designs and facilitates a classroom culture that promotes student preparedness, engagement, self-advocacy, perseverance, and collaboration | Preparedness: Starts with a clear agenda setting context with last class and into future classes Engagement: Plays Sam Cooke, ask kids to talk in groups about why that song at this point in their lessons (Civil War), some share out and class discussion. Lots of small group interactions |

I often will start a course and each new module with an overview of our class schedule and the topics associated with each day. This is an area I would like to improve in explicitly referring back to more frequently. It could be a simple addition to the daily agenda seen above. I have been better about this component in more skill-based progression as seen in Classroom Culture (5) designs and facilitates a classroom culture that promotes student preparedness, engagement, self-advocacy, perseverance, and collaboration.

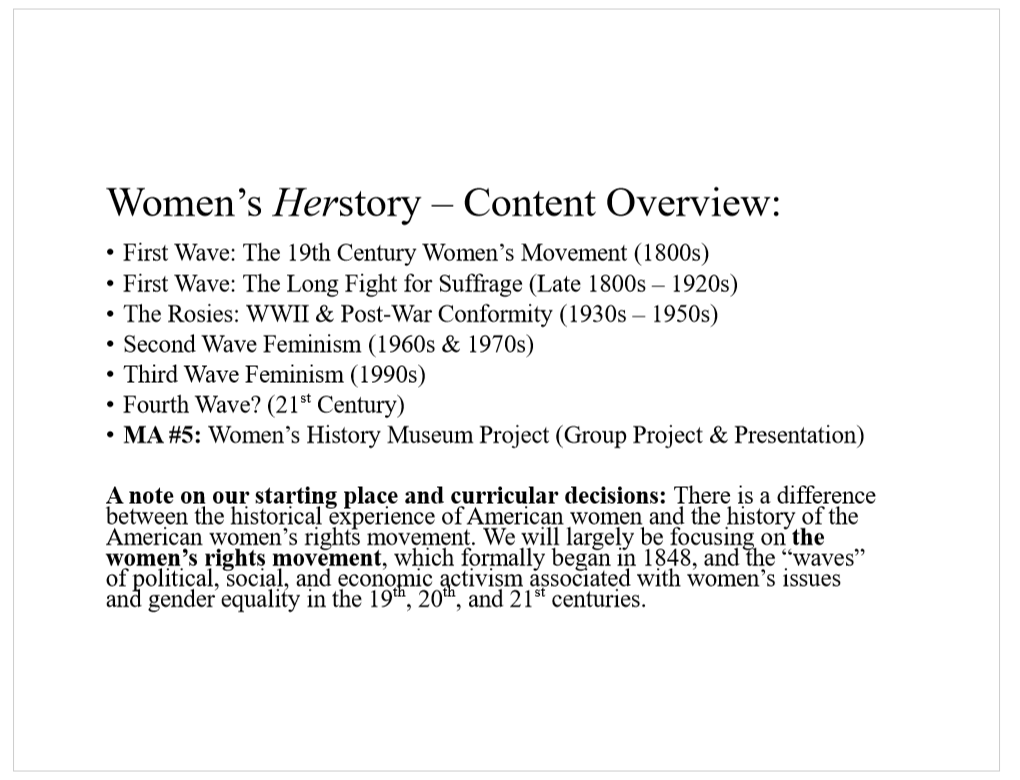

There are times where this is happening on a frequent basis like in our current Women’s Herstory module in US History where we look at, summarize, and compare the first three waves of feminism. However, this has served more so as review and/or to allow for comparison between content.

(2) designs and implements varied activities in each class period

Facilitating a student-centered classroom requires a diversity of varied activities. At times, I will need to provide context on what we are learning or lecture on key concepts and ideas so students are equipped with the content knowledge to start their inquiry. A majority of my lesson is centered around student discussion, which will quickly transition from partner turn and talks or think-pair-shares to small group discussions to whole class debriefs. Additionally, we will do jigsaws, structured academic controversies, and gallery walks.

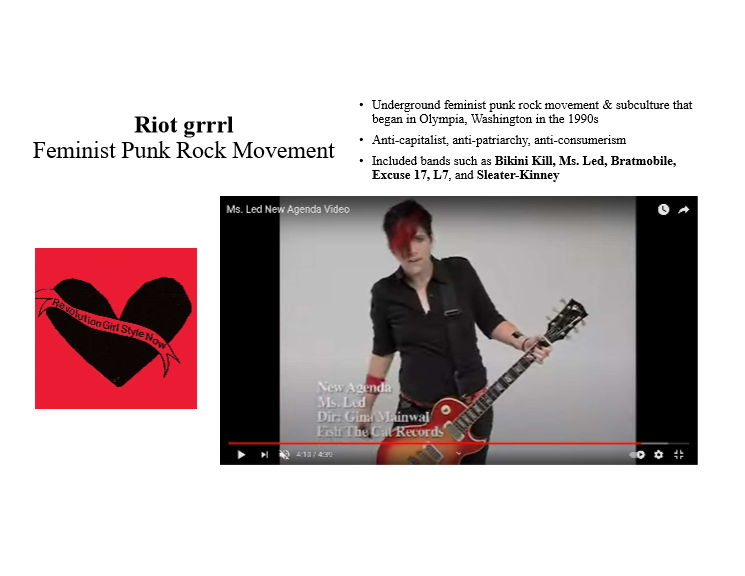

This day in US History covered a lot of content. Starting in our 4th module, each day starts with a song that connects to that day’s content.

As we were transitioning into our Third Wave Feminism study, we started with Ms. Led by Riot grrrl and asked the students to think about how this song represented the characteristics of Third Wave Feminism.

As were were approaching the final, we had students check in with their groups for their Women’s History Museum project. Then we debriefed the homework before reviewing the previous waves of feminism we had already studied. In order to add more elements of intersectionality, students analyzed The Combahee River Collective to understand the female voices who were left out in the movement, which culminated in a whole group discussion. To wrap up, we examined Phyllis Schaffly and the countermovement against the Equal Rights Amendment through several video clips and discussion questions.

Often times, students will participate in an inquiry to arrive at their own conclusion. However, every now and then it is important for students to adopt a position that may not be their own. One of my favorite activities to achieve this is a structured academic controversy. In Origins, students were tasked with making arguments that Athens either was or was not a democracy.

Case: Was Athens a democracy?

Team A will argue: YES, Athens was truly democratic.

Team B will argue: NO, Athens was NOT truly democratic.

Procedure:

25 minutes: With your partner, read through the sources provided and find evidence. Build your argument with at least four pieces of direct evidence from the document set.

5 minutes: Team A presents their argument while Team B takes notes. Team B then summarizes Team A’s argument for clarification.

5 minutes: Team B presents their argument while Team A takes notes. Team A then summarizes Team B’s argument for clarification.

10 minutes: Everyone can abandon their positions and as a group of four, try and build consensus.

*Note: You will submit your initial arguments from your assigned position and your group consensus on Canvas.

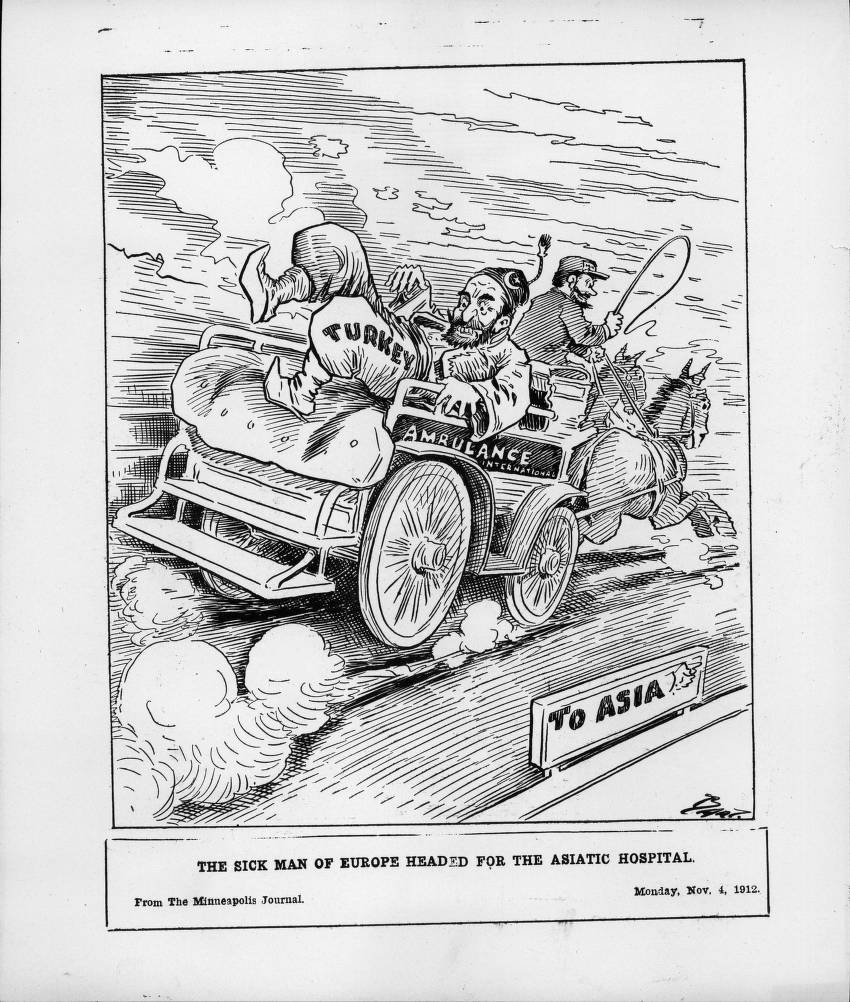

Here is the agenda from the first day of our second module in Middle Eastern History.

- Opening Activity- Political Cartoon Analysis and Primary Source Analysis on Ottoman Empire

- Context on 19th-20th century Ottoman Empire

- Source Analysis: Young Turks

- Context on Arab Revolt & The Hashemites

- Inquiry: Hussein-McMahon Correspondence & Sykes-Picot Agreement

- What will the future hold for the post-Ottoman Middle-East?

To set the stage for the module, students go to select from a variety of political cartoons to analyze that showcased the state of the Ottoman Empire on the eve of WWI.

Since this was the first day of the module, students had very limited background on this topic. Through their analysis and comparing the various political cartoons, were were able to generate a class-wide hypothesis on the state of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century. I then transitioned us into a contextual overview of the decline of the Ottomans where I was able to incorporate some of the student ideas from the opening activity. Students then examined a primary source from the Young Turks, I provided some context on the Great Arab Revolt during WWI, and students were presented with an inquiry that would set the stage for the rest of the module.

- Why did an internal Arab Revolt take place in the Ottoman Empire during WWI?

- How do the Hussein-McMahon correspondence and Sykes-Picot Agreement differ?

- Make a prediction– How will the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and land division at the end of WWI impact the Middle East?

Here, students had to make sense of the all of the secret dealings taking place as Western powers were preparing for the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and a post-WWI Middle East.

(3) brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities

With a variety of activities in each class, transitions help with efficiency and clarity for expectations. On a consistent basis, students are usually transitioning between either partner work or a small group discussion to a whole class debrief. Out of respect to their time and wrapping up, I will narrate a 3-2-1 countdown for the transition. To just start talking without having their attention yet would put students in an unfair position of either cutting them off, missing key information or instructions, and/or expecting them to stop on a dime. This simple narration gives them a step-by-step transition: “Let’s start get ready to debrief whole group in 3. Wrap up our conversations in 2. Bring our attention back up front in 1.” and then pause until I have everyone’s attention. This allows students to finish their discussions, feel respected, and have clarity on the expectations. I can also ensure I have each student’s attention for the next set of directions.

Snippet from Katie Dodd’s observation:

| brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities | Yes, offered context and information about transitions between topics and activities, as well as connecting to past classes as well as future content. Clear connections established between KKK, Emmett Till, lynching and anti-lynching laws |

(4) ensures that students are using technological tools effectively

So much of what we do at EPS is on the computer. It can be difficult to find a balance between technological tools and opportunities for distraction. All of my course materials are organized in OneNote so it requires students to have their laptops open most of class. The basis of my classroom management is circulation. I will average 2-3 miles a day while teaching in two 70 minute classes. This allows me to monitor student use of technology and follow up one-on-one if needed.

When having to address student behavior with technology, I try to invite them into the problem solving process. I let them know that I am not upset and they are not in trouble, but that we need to find a better way to move forward so they can more fully engage in class. One such conversation earlier this year in one of my 9th grade classes, the student was open and honest that staying focused when A block was the last period of the day was particularly hard for him. We devised a system where I would give non-verbal cues to him like while circulating and tapping the desk so to avoid any attention from his classmates. He saw this as supportive rather than punitive and was able to quickly redirect to meet expectations. Over the course of the term, the need for this became less frequent as he was building in the capacity for more self-regulation.

(5) concludes class with a summary and clear tie-in to the next class

Admittedly, this is an area for improvement. Often times 9:40, 11:05, 1:35, or 3:00 sneak up because I am caught up in whatever activity we are currently in. I pay attention to the clock to try and reserve a few extra minutes at the end to conclude and tie-in to the upcoming class, but sometimes this moment feels abrupt.

There have been various routines I have used in the past at both EPS and in previous schools to combat this, like reserving the last ten minutes for a reflection, course work assignment, or some other form of independent activity.

Snippet from Katie Dodd’s classroom observation:

| concludes class with a summary and clear tie-in to the next class | During class, gives a preview of what will be done on Tuesday or next week with examination of Brown vs. Board of Education; hw is listening to a podcast and answering questions; instructed students to keep Plessy v. Ferguson in mind |

Differentiated Instruction & Assessment

Differentiation. It’s a BIG word in education. It something that feels impossible to master. How can I tailor every aspect of my class to every need of every student? Impossible.

I entered this process identifying differentiation as an area I would like to continue to improve. Perhaps I do not give myself enough credit for all that I already do, but I struggle to escape this aforementioned idealized sense of differentiation. With that unattainable relationship to differentiation, it keeps it at the forefront of my mind as it is an area I can always improve. However, as Jamie Andrus always wonderfully showcases at PDD: simple additions can equate to huge outcomes in student growth.

Starting my teaching career in public charter schools, the focus was on this grandiose mission of “closing the achievement gap.” My former students, mostly first and second generation immigrants from Latin America, were at various levels within English Language Acquisition, so differentiation for ELLs was something I always had to account for. This would include adding visuals, word banks, sentence starters, concept maps, providing guided notes, anchor charts, etc. It would be fair to assume that class sizes would be smaller to support that variety of needs for English Language Learners, my classes would generally having anywhere from 25-32 students in six out of eight periods in a day, there was not enough time or resources to accomplish this objective. In our AP for All curriculum, I utilized data driven instruction to best support each individual student in preparation for the AP exam at the end of the school year. Through tracking specific skills on the document based question, short answer questions, and free response questions as well as mastery of the content from the various world history periods, I was able to design individualized review sessions so students could make the quickest and most efficient gains in skills and/or content mastery before the AP exam. In broader reteaches, I would employ a technique called active monitoring in which I would address the misconception, answer clarifying questions, model an exemplar, and have the students attempt the task. I would then individually check each student’s work every step of the way. If a student passed, they received a check and could move on to the next step. If not, they would receive a symbol letting them know what needed to be fixed and would continue to address this issue/step. I carried a clipboard and collected data live on student mastery. If the broader class was demonstrating mastery, I would pull the small group who was not and do another reteach. If the broader class was still not demonstrating mastery, I would stop everyone, regroup, and address the misconceptions and trends I was noticing.

These practices were very effective in test prep. As much as the evolution of teaching history has transitioned from rote memorization to emphasizing critical thinking and the skills of the discipline, a lot of these practices work best in a discipline like math when implementing formulas or doing problem-solving. The fact that EPS does not utilize an AP curriculum coupled with the sort of “drill sergeant” feeling of this, I’ve had to consider these type of practices in this new context.

EPS is built in a way where the individual needs of the student can be more at the forefront of the learning experience. As educators, working with a class capped at 18 students is much more manageable when it comes to designing lessons with the intent to reach all learners. Additionally, teaching four sections out of eight opens up the opportunity for more one-on-one meetings with students to address misconceptions, provide feedback, and help students with content or skill related issues. The practices I adopted earlier in my teaching career continue to help in specific tasks and objectives at EPS, but the level of autonomy and creativity EPS permits and encourages beyond standardized testing has prompted me to rethink my purpose in differentiation.

At the heart of my practice has always been relationships. Knowing my students, building trust, and forming meaningful relationships allows me to better understand their needs, what types of activities, and the level of rigor is going to work best. I can design assignments, projects, and assessments with what is best for the group and allow opportunities for each individual to leverage their strengths and interests.

(1) considers and addresses each student’s learning profile

Differentiation has to start with knowing who your students are. I start each term reviewing each student’s learning plan and often times will send out a survey to get more insight into each student. I intend to make this a more consistent part of the start of my courses. I have primarily taught the class of 2024 the last few years and, while there would certainly be value in collecting survey information each school year, I admittedly have been less consistent in using a student survey as a result. Next year, I plan on developing a second survey that I can use when I have taught students previously.

In addition to these modes of better understanding students, I also attend hand off meetings to collect insight from former teachers. Often times, 9th grade humanities teachers will meet in between trimesters to report any insights of particular students as class rosters shuffle. This information is invaluable for support, seating assignments, discussions, assignments, skill development, etc.

At the end of the day, nothing is more impactful than building relationships.

When students feel known and cared about, it has drastically improves the classroom experience and learning outcomes.

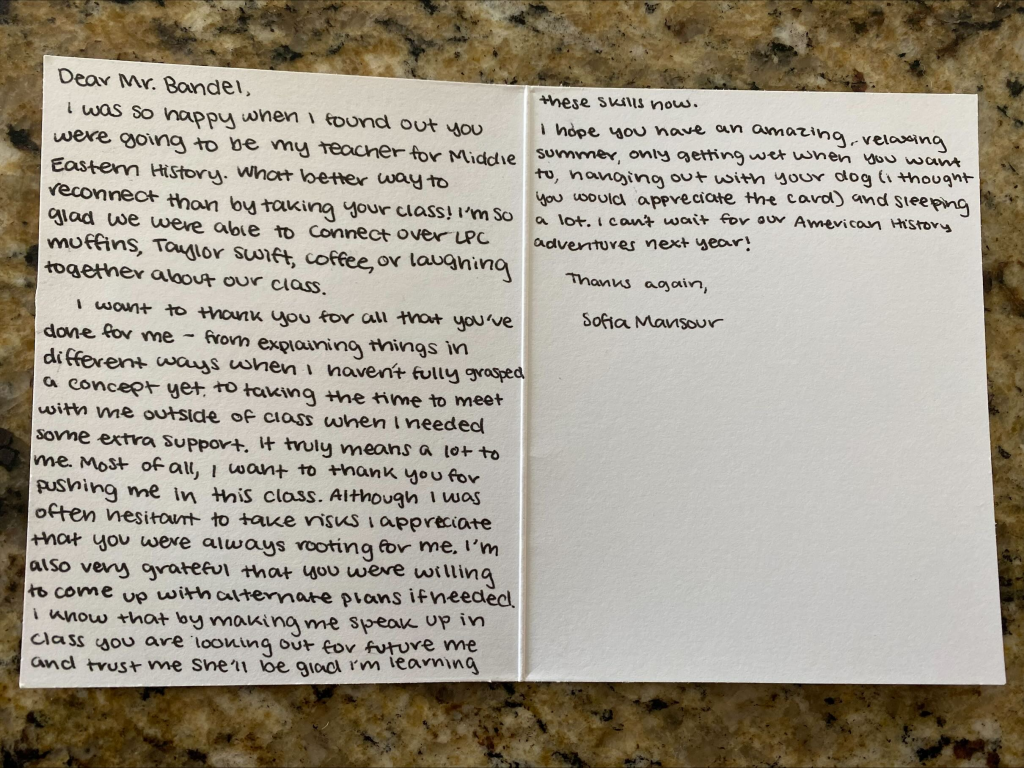

As the 2022-2023 year was winding down, I received this note of appreciation from a current student in my Modern Middle-East history course. While this student has gotten better at self advocacy and asking for help, I’ve learned to pick up on her signs of needing help and checking in. Even when she approaches me, she will not always have clarity on what she is asking for. I have had to learn that sometimes all I can offer are a few ideas for the student to think about as they find their own clarity of what they need rather than trying to ask several questions to get to the root of the issue.

(2) designs class activities and assignments that engage and accommodate for both individual students and a diverse group of learners

A typical day in class is an inquiry style lesson centered on an essential question with a diverse set of primary and secondary sources. Throughout the lesson, students participate in several discussions shifting from think-pair-shares to small table discussions to whole class debriefs. I try and incorporate different ways for students to process information and I would like to continue to find new ways to do this moving forward.

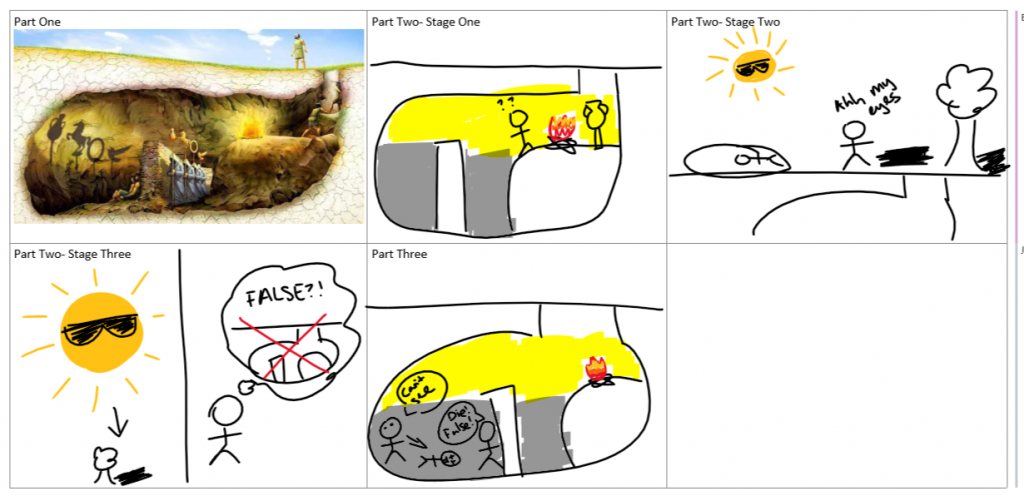

One example is the storyboard students create in preparation for their analysis and seminar on Plato’s Allegory of the Cave:

Here, students are able to visually represent the allegory in order to consider what each stage in the freed prisoner’s journey means and represents. Following this comprehension step, students are able to now to access the higher order thinking questions and prepare for their seminar discussion.

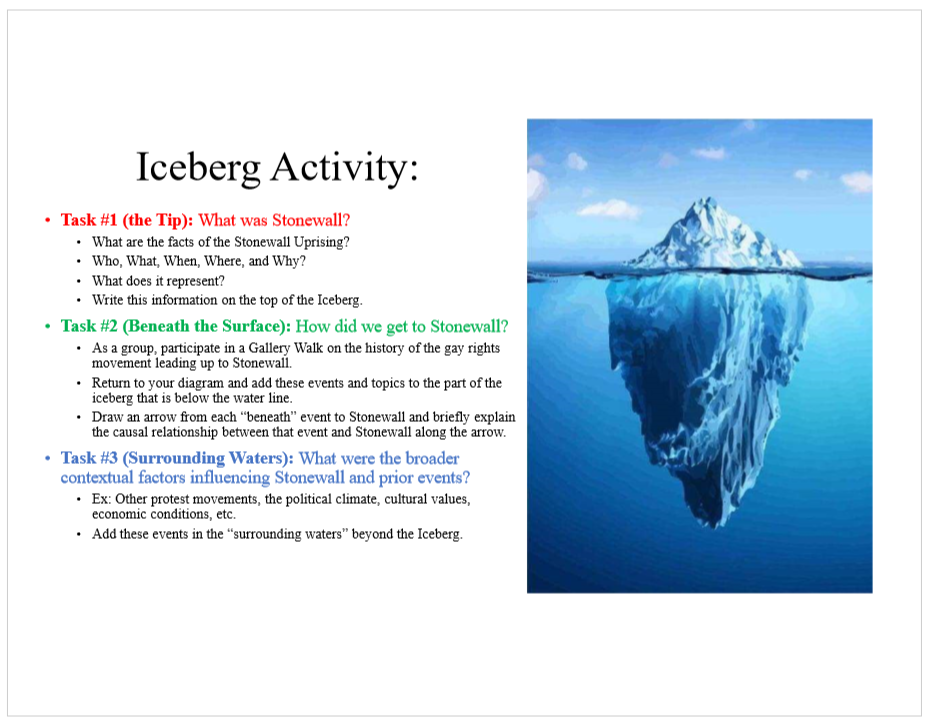

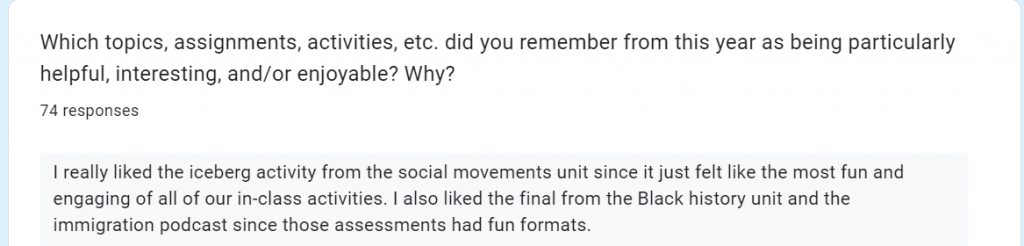

In US History, we wanted students to understand the importance of the Stonewall Uprising as the starting point for the contemporary Gay Rights Movement. In this activity, students debriefed their homework on Stonewall and jotted down as much as they recalled in the tip of the iceberg. However, we wanted students to recongize that Stonewall was the culmination of over a century of policies and cultural changes. Students participated in a gallery walk and had to consider a variety of sources ranging from sodomy laws to The Lavender Scare to the Hayes Code to APA/DSM Categorization and connect these seemingly unrelated historical moments to the Stonewall.

In fact, in our end of year survey, a particular student said this was the most memorable activity from the entire year in US History:

(3) builds in opportunities for each student to contribute during each class period

Facilitating a discussion-focused classroom provides a wealth of opportunities for students to contribute. However, this does not necessarily work for all learners right from the beginning. For more introverted, anxious, and/or shy students, this can be quite intimidating and thus requires opportunities in a variety of formats as well as building trust, coaching, and strategically planning for these students needs. It is very easy to fall into the habit of calling on the very first student with their hand up or to rely on the students who are most eager to participate, but you also do not want to lose their engagement either.

Some of the strategies I employ to address these issues are:

- Utilize wait time– I will tell students to hold off on raising their hands before I let them know that it is time to. I use this to give enough time for students to process based upon need while also attempting to prevent those who are slower readers/processors to not compare themselves to their peers by seeing hands go up much earlier than they are ready.

- Set a minimum raise hand requirement before we discuss like “I’m looking for at least 5 hands here.”

- Circulate and identify particular students to answer specific questions– Some students just need confirmation that they have the right answer or a great response before they feel confident enough to share it. So as I circulate around the room during partner, small group, or independent work time, I will check in with students who do not participate as often and let them know with a genuine excitement about how wonderful their idea/response is. I then ask for their permission if I can call on them for question X.

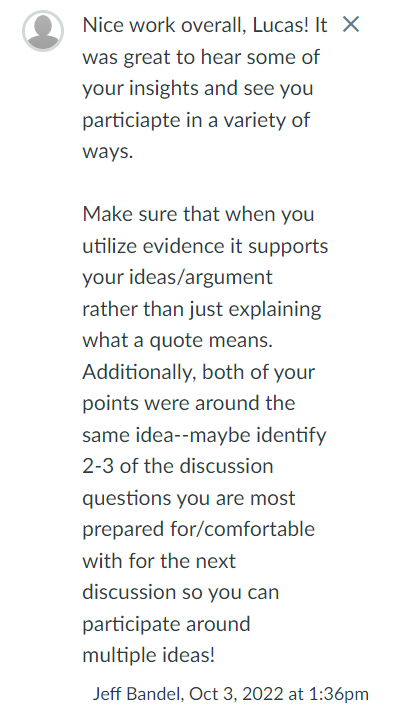

I try and partner with student around Harkness discussions to help them insert themselves into the discussion. It can be very difficult to contribute when others have already stated points similar to those that you prepared or process what is being said and offer a new idea on the fly. For this student, I provided feedback on identifying 2-3 questions ahead of time that they felt most confident in or comfortable answering. Before the next Harkness discussion, I will meet one-on-one with these individuals and ask them which questions they would like for me to come to them first for. With this strategy, students can contribute what they have already prepared and start the conversation before it starts to evolve. Furthermore, since the particular prompt starts with them, they tend to make multiple contributions for that particular question because they have already offered ideas and are not worrying about what they are going to say.

I received this email from a student the night before a MA and we agreed to meet the following morning before their discussion. We reviewed what they were able to get done and I was able to provide feedback on their ideas while also identifying their strongest responses. We then agreed to the aforementioned strategy of identifying which questions they would be the first to respond to.

(4) provides alternative explanations of course concepts

“Bell Ringers”/”Do Nows”/”Opening Activities” are a wonderful way to activate the learning for the day and capture student interest. This can also be utilized for a formative assessment, check for understanding, and re-teach. While I usually open class with the former, I will often use it for the latter strategically.

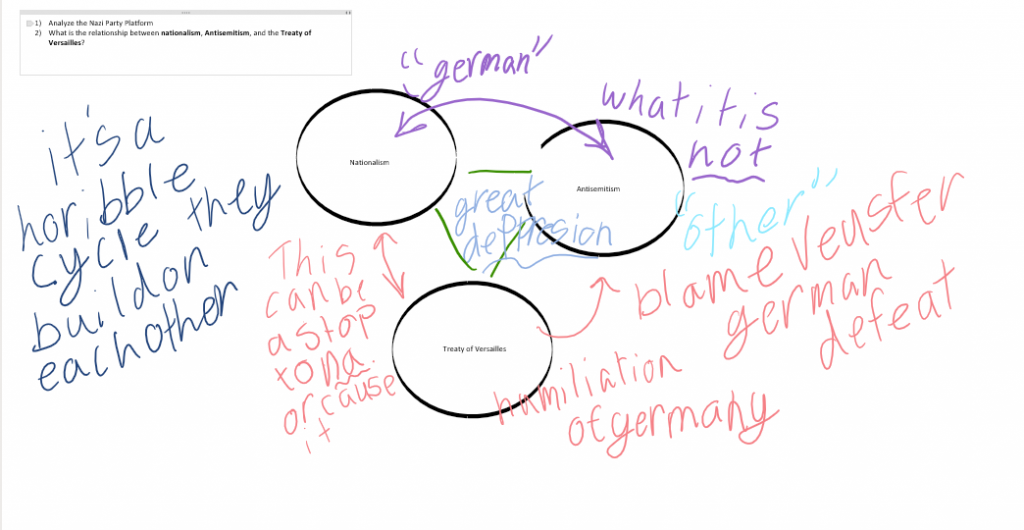

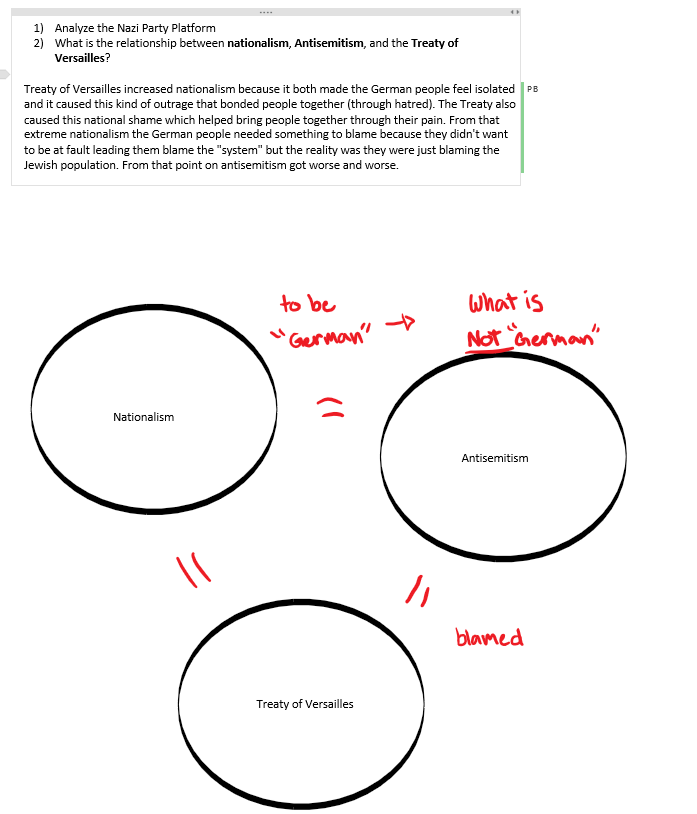

In the fall in Boundaries (history), students had been introduced to and working with some of the bigger course concepts for a few class periods. Before we could transition into analyzing the Nazi party rise and ultimate seizure of power, I needed to ensure students understood the concepts, but more importantly how they related to one another. I asked students to independently construct a concept map between these three concepts with explicit links and explanation of the relationship between all three.

This allowed us as a class to review the concepts, analyze and contextualize the connections, and correct misconceptions. I first surveyed a variety of student responses and noted their ideas on the board. Any discrepancies or contradictory ideas, I prompted students to discuss and consider what ideas and explanation they agreed with and why. Hearing from one another allowed alternative explanations while I would then conclude with succinct key points and ask the students to make any revisions to their original work.

Student work samples:

(5) adapts instruction based on formative assessment

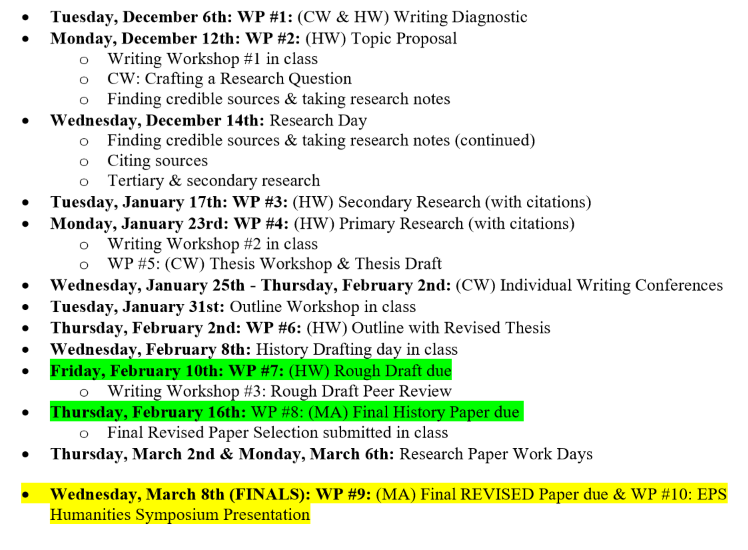

In the 9th grade winter trimester, the focus for both Migrations and Exchange is the term long, argumentative, research essay. This is a highly scaffolded and feedback oriented process with deliberate steps to help students improve as writers.

Here is the step-by-step calendar of assignments for the 2022-2023 iteration of the Exchange (history) course:

I had taught several of my current students in the previous term, but roughly 50% of the students are new to me, so it is imperative to see where they are entering the course as writers. To begin, I assign a diagnostic related to the content we have already been covering in class. Students are asked to consult a set of primary and secondary sources to construct an argument regarding how the Renaissance has changed humanity’s view of itself. The diagnostic serves as a temperature check for the class as a whole while allowing me to both track individual growth and plan lessons to target gaps in student skills.

Here is the tracker for key skills from the initial diagnostic for my B period section:

As the data suggests, there is room for growth in all the categories. Since the thesis statement is an earlier assignment in this process, I start with incorporating thesis focused activities in daily lessons. One such example can be seen here:

Thesis activity:

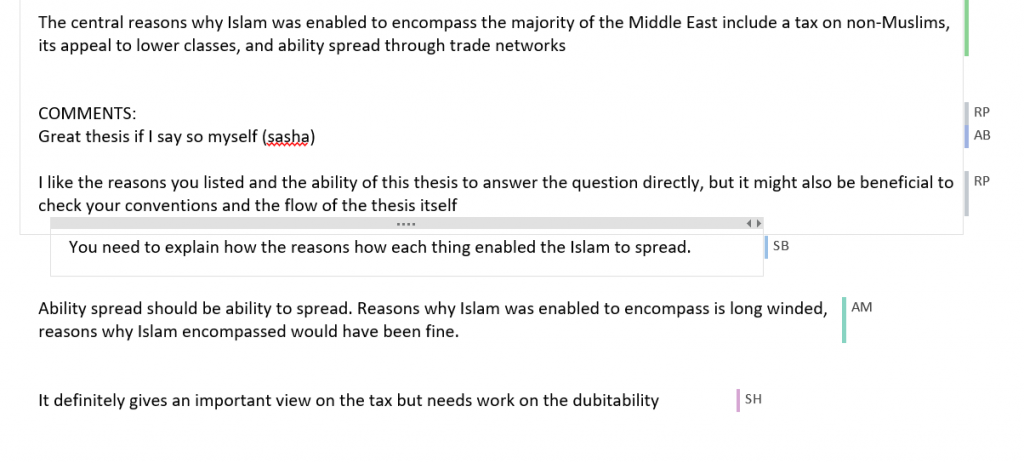

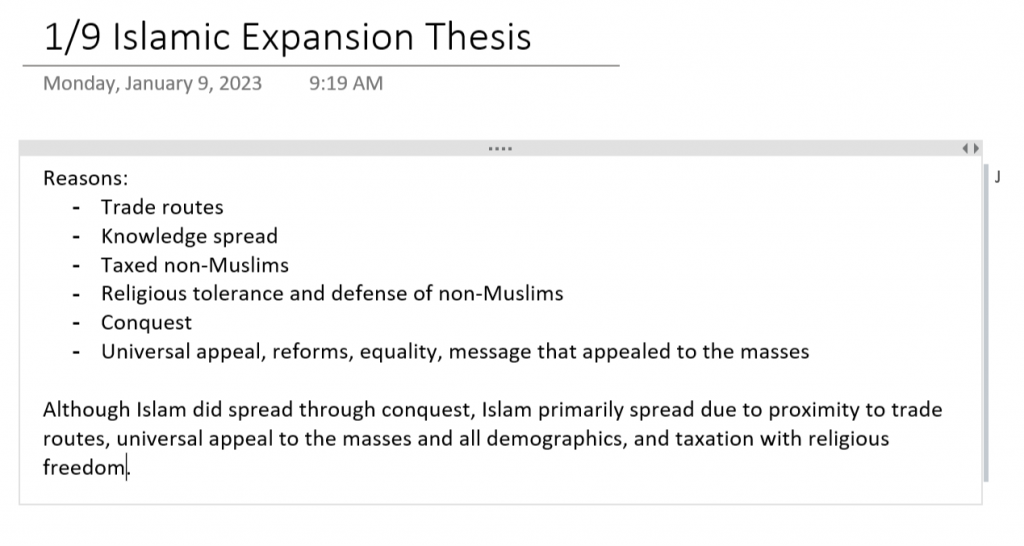

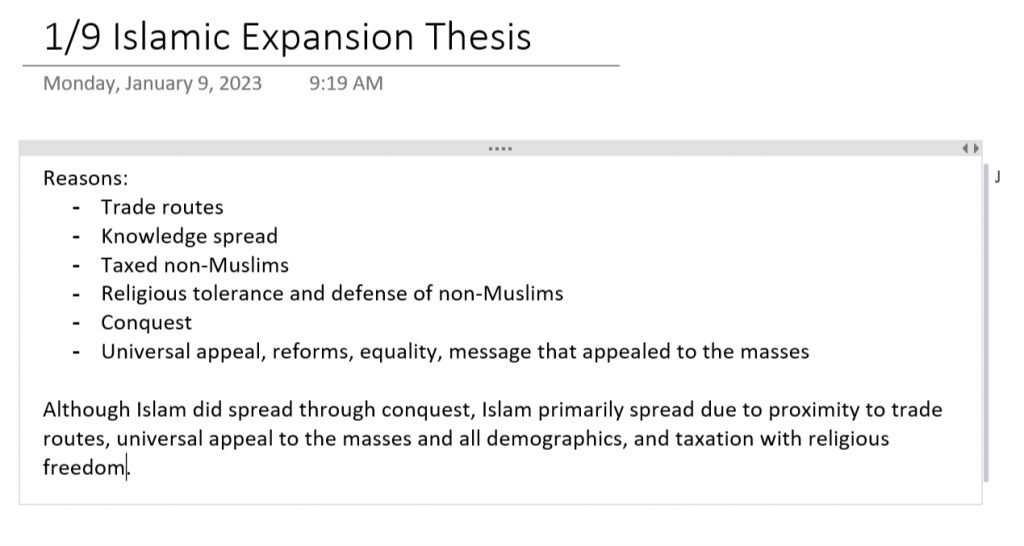

Step 1: Students consulted a variety of primary and secondary sources on the expansion of Islam and were tasked with constructing a thesis statement after analyzing and synthesizing. Partners produced a thesis statement in the collaboration space and then were provided time to leave feedback on one another’s work as seen here:

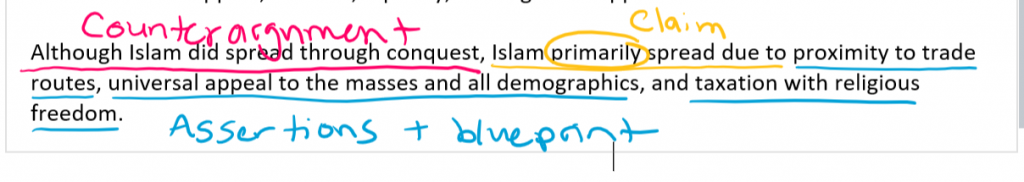

Step 2: After looking at one another’s work, we returned whole class to debrief what we were noticing and ultimately construct an exemplar together.

Step 3: Identifying the components, so the students have an exemplar to refer back to and check their own work against.

This activity helped students at all levels depending on their diagnostic performance. Students who were at a more beginner level got to work with partners and think through the creation of a claim, provide and receive feedback in the collaboration space, and work through step-by-step exemplar creation. Students who were categorized more intermediate, generally, had a claim present, but it was either fairly simple or missing other components. They were able to practice adding a list of reasons as well as a counterargument to increase the complexity and nuance of their overall argument. Students who were categorized as more advanced, generally, produced clear claims supported by relevant reasons. They were able to practice adding more specificity, nuanced language, and a counterargument to their thesis statement. While there is always room to improve, students have consistently improved in their thesis writing throughout this process. Major gaps have been addressed and skills have been refined. Most importantly, students are able to engage with one another’s work during peer review and give precise and targeted feedback to each other, which demonstrates their understanding of the components and criteria that make a quality thesis.

The area that is always the hardest jump for 9th graders in particular is moving from summary to analysis. As seen in the data from the diagnostic, 68% (11/16) of students struggled with this skill. To help address this issue, I designed and implemented a lesson on analytical writing. Students have been able to demonstrate analytical skills especially in image based activities like analyzing art or propaganda posters, so that is where we started. After receiving feedback that this was an area for improvement, this also instilled confidence because they were able to see there are already ways in which they demonstrate strong analysis. I selected two of my favorite commercials and asked students to first identify the intent of the commercial and then we re-watched to debrief how the commercial fulfilled this intent.

From this discussion, we were able to debrief the analysis of the two specific commercials to have a broader conversation about what it means to analyze. I then transitioned us to an overview of analytical writing, various examples of weak analysis, and asked students to look at a variety of examples and identify what form of weak analysis each was demonstrating.